(some language may be off-putting)

In the 30s my father’s father built two houses at the edge of town. He lived in one and rented the other. By the 60s, the houses were in the middle of town and the mile-long street was a bustling hodgepodge of enterprises and homes.

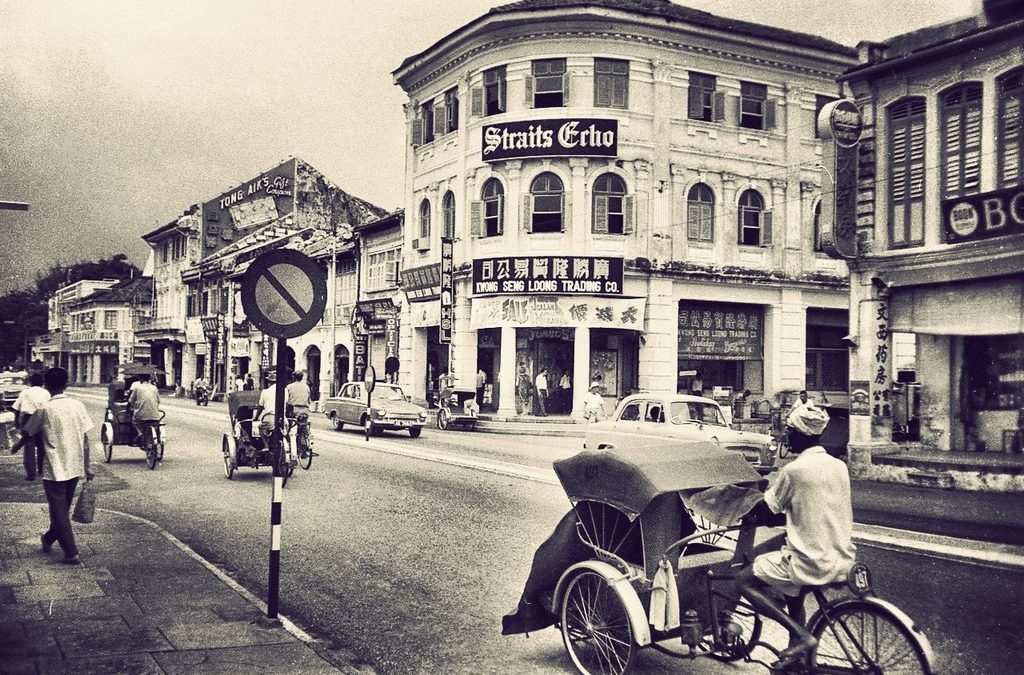

One end was a wet market, the other a mosque. In between there was an English kindergarten that my brother attended, he was a boy and so, worthy of the investment; a shack selling Indian sweets and tea, a dilapidated wooden hut on stilts under which bicycle tires were repaired, and stretches of newly built Chinese shop houses. These were linked double-story concrete buildings with a shared five-foot covered walkway decorated with colorful ceramic tiles. Downstairs were businesses; appliance and radio repair shop, rattan shop, joss stick maker, sundry shop, acupuncturists, Chinese Association Hall, and a coffee shop that sold fish noodle soup and beer. Upstairs proprietors lived with their families.

Our two houses fronted Seang Tek Road and backed onto Malacca Street which had pretty much the same assortment of buildings other than a Hindu temple and a whore house where American GIs R&R from Vietnam. The whore house was catty-corner from us. The men arrived in uniform on trishaws, waving and whistling to us kids.

There were several older, multigenerational homes like ours on both streets, where four or five blood-related families lived under one roof. One home housed a village! It was a sprawling white wooden structure on low stilts close to the street. Their French front doors were wide opened, showing an empty hall where kids sat cross-legged studying the Quran in the afternoons after school. They were Boyanese from East Java. The kids played only among themselves. We turned up our noses at how so many of them lived in one house, we only had four to six families at one time.

There were two large halls upstairs in our house where transient relatives from “the country,” Yemen, lived, sectioned off behind makeshift curtains. A narrow L-shaped hallway, the landing area for the stairs, was popular with one family. Downstairs sometimes there was a bed in a corner where a young man who worked for one of the uncles slept. The families lived for months or years until they settled in their own homes.

One family had a dad who was good with plants and animals. The dying shrubs along the fence perked up with fish rinse and fish guts, and for a brief time, we had a pet long-tailed macaque called Chicu. Another family had a daughter the same age but the opposite of me. She was soft-spoken, gentle, and smiled a lot. We did not do much together, but I loved her softness and felt close to her. Her father spent his evenings hugging our cabinet-sized radio dialing up Egypt, straining his ears to pick Arabic news from static.

Our house was tucked back by a long driveway that curved under a tall porch. The large bare and dusty yard had a giant rose apple tree in the front, next to a gate of spear-like metal railings, ten feet high in the middle where it opened, and shorter on the sides. Cement benches formed a bridge entrance over an open drain. A high cement wall rose from the drain, lined with small round holes to peek at the outside world. At the top of the wall, sharp green, brown, and blue broken glass deter intruders. An outdoor bathroom made of galvanized zinc sits in one corner sharing a wall with a shop house. The grey weather-beaten and peeling wall continues to the porch where the shophouse end, replaced by an alley that borders our house whose windows open to the alley. When television came to Penang and we were the first house on the street to have one, kids gave me marbles or cards to open our windows.

Up until the early sixties, the night-soil man came along this alley to the very back of our house, pulled open a corner flap, and emptied the pail we defecated into squatting on a raised platform. He carried two huge pails on each end of a pole. The contents he sold to the vegetable seller. People dived into their respective homes when he passed. When he was done in the alley, someone shouted: “line clear!”

My grandfather owned paddy fields, coconut trees, and a car that looked like a bun on wheels, one of the first cars on the island of Penang. He owned a jewelry store with a partner. The day he died, his partner emptied the safe in our house and we lost all the jewelry and the store. My grandfather was in his late forties, my father was eight. The partner gave my grandmother marketing money for a while and then the money stopped. As adults, my father and Fourth Uncle spat every time they passed the jewelry store.

We had all the rice and coconut we could eat, stored under the stairs in a dank, dark room. The family lived off money from sharecroppers and property rentals until the land and the rentals were sold. When the last of the rice and coconut arrived from Grandfather’s land, it was a windfall! We got more than three times what we normally received and soon the already musty storeroom smelled of old rice, rotten coconut, and rat shit. The rat shit the same shape as the rice but bigger and black.

Elder relatives told us that if our grandparents were alive, we would not look scruffy as we did, our clothes would be starched and pressed, the girls would wear gold bangles halfway up our arms and gold anklets with bells. I was relieved. I did not want to go about with bells like a Hindu cow, though the thought of a glorious, bling-bling past, was exciting and exotic, especially in light of what was real—Eldest Uncle was a rogue, my father, Second Uncle, was rogue-ish, Third Uncle was mentally challenged, Fourth Uncle was a wimp, Youngest Uncle was in England, and the two aunties being women had no say. By the time the car, paddy fields, coconut trees, and the last two houses on Seang Tek Road were sold, the two houses replaced by twelve Chinese shop houses, six facing Seang Tek Road and six on Malacca Street, my father’s rightful share plus Youngest Uncle’s “borrowed” share, bought my father a two bedroom link house in the suburbs miles from the others.