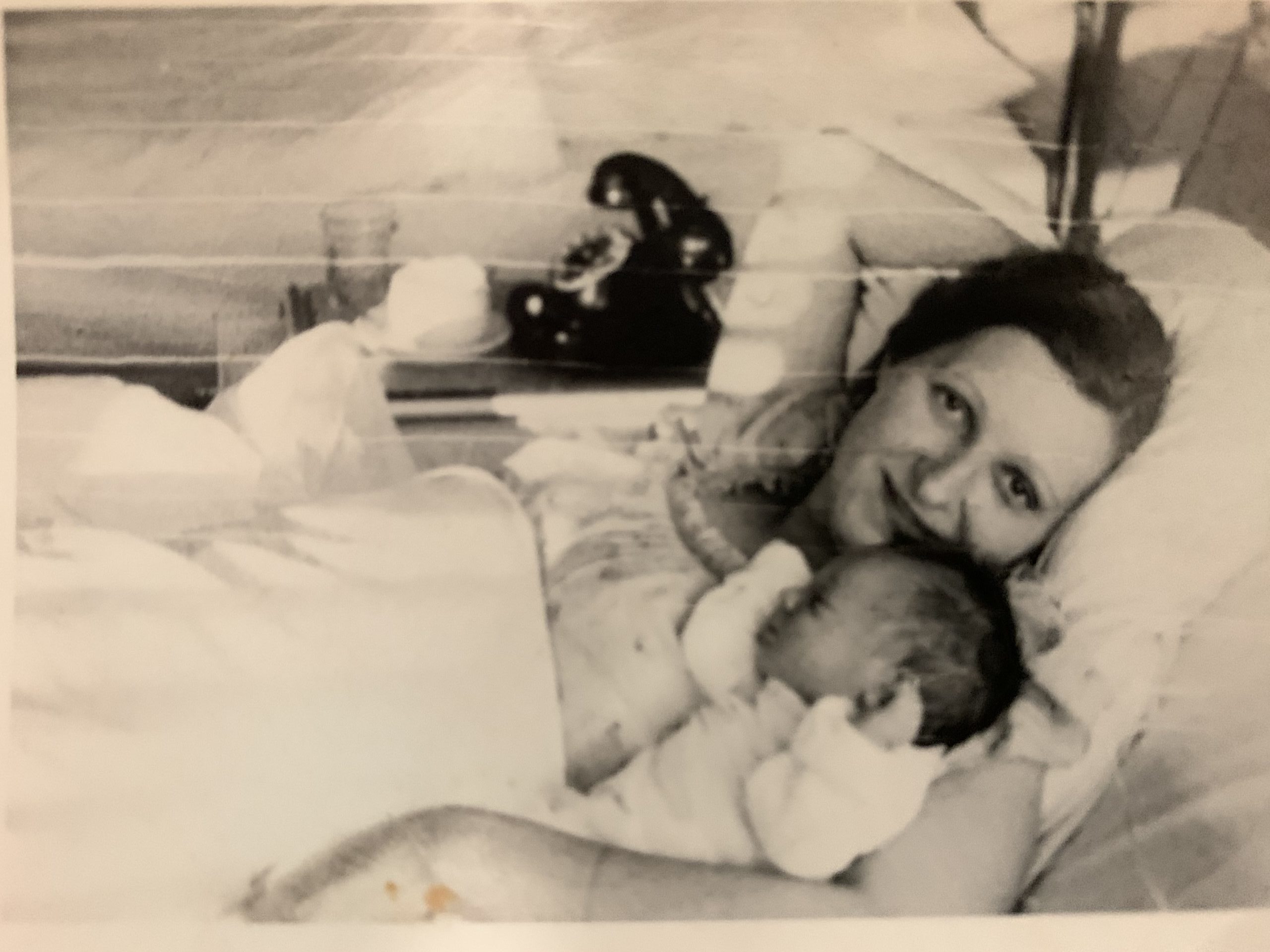

My mom Edeltraud Hildegard Janiel, her mom, my Oma, and my Aunt Mimi

I have been an elder or, speaking politically correctly, a senior citizen for some time now, taking advantage of discounts for concert and movie tickets and playing the age card when all other attempts at persuasion fail. I have generally not been much inclined toward looking to the past. I live in the present and still look toward the future with curiosity. Then recently, a very ordinary thing happened, that prompted me to think about my childhood during the turbulent times of the rise and fall of Hitler’s Third Reich. A dear friend gave me a book, which in turn gave me the impulse to start the ball rolling.

As I take up my pen, I realize that the decision to write these memories was actually already born with the death of Marian, the oldest of my beloved first cousins, almost a year ago. He was the first of my generation to die from natural causes. That was a wake-up call. So, I try to rise to what seems almost an obligation. Describing the vignettes that stand out in my memory is the easy part. The more difficult task is stringing them together into some kind of narrative. The pieces do not always fit together neatly. But the previous generation is all dead. They can no longer be consulted for answers or clarifications. Imperfect though my recollections may be, as the line between “remembered” and “remembering to have been told” blurs over time, it is up to me and no one else. Past the threshold into the ninth decade of my life, the time is now or never.

The things I can remember are purely memories of my experience of family life in turbulent times. Of the background, which is by far the more interesting, I had only a child’s view. Even though I lived through them, I find that I know little about the sequence or extent of the events that reshaped Europe after almost destroying it. Modern European history, especially German history, was not taught in German schools after the end of the Second World War when I was a student there. Was it that we could not face what we had allowed happening? I wonder if this period is taught in German schools today, or has it been left to writers like Gunter Grass to be the conscience of a whole nation and to atone for their, for our collective guilt?

As I begin to write, it becomes apparent to me that, with all of her faults and weaknesses, my mother emerges as the heroine of this piece. I am dedicating my effort to her memory.

I was born in the prestigious Women’s Clinic in Gleiwitz, Upper Silesia, and lived with my parents in the heavily industrialized city of Hindenburg. My father, Georg Josef Janiel, was a talented structural engineer and a successful businessman. At a relatively young age, he joined as a junior partner, an established firm that designed and built steel structures below and above ground. In peacetime, that meant the construction of bridges and multi-story buildings. Following a terrible depression, the company thrived in the economic boom of the mid to late 30s and would thrive even more during the early years of the war. The firm expanded into areas required by the war effort, such as repairs not only on structures like bridges but also on tanks and locomotives. When my father’s senior partner, his “Compagnon,” wanted to retire, my father was able to buy him out.

My mother, Edeltraud Hildegard Janiel, nee Widawski, was his 10-years-younger trophy wife. While she certainly was not beautiful, she was pretty enough, sweet-natured, charming, and very elegant. And could she cook and bake! My mother had a beautiful singing voice and loved using it to teach me children’s songs and lullabies, to accompany the music from operettas and popular hits on the radio, and to sing at Christmas, not just “Oh Tannenbaum” and “Silent Night”. She also taught us to sing the hauntingly beautiful Polish Christmas carols of her own childhood.

I arrived five years into the marriage, on September 2, 1937, longingly awaited, especially by my mother, who had begun to suffer feelings of inadequacy due to her barrenness, painful even more so after some relative on my father’s side had said, in her hearing, that a tree that bore no fruit deserved to be pulled up and thrown away. She had had an earlier pregnancy, which had ended in a miscarriage with medical complications. At that time, the doctors told her it would be unlikely that she could ever have children.

One of the family stories, often told by my mother, was about my arrival. My father was at work when she felt the first contractions. When she became certain that this was not going to be a false alarm, she called my father, and he famously said to her: “You have to hang in. I will be there just as soon as I can.” I would remember those words some sixty years later when from her bedside in Germany her doctor called me to tell me that I needed to come sooner than planned and then handed the telephone to her, and I spoke these very words: “Mother, you need to hang in. I will be there just as soon as I can.” Such dreaded calls always come around midnight. At 5:20 am I was on a flight to Germany and I was holding her hand when she died.

I was born small, less than six pounds, and had a hard time getting going. If my mother was disappointed that I was neither blond nor blue-eyed like the photos of her own childhood but looked more like a pale-skinned, dark-haired Gypsy foundling, she did her best not to show it. Instead, she lavished love and care on me and dressed me up like a little princess. Although Hitler was already in power as the elected Chancellor of Germany and dark clouds were gathering for those who could see clearly, World War II had not yet broken out. I would later brag that I was of good peacetime quality. Already by my second birthday, the war broke out. But for the time being, life was still full of bliss.

My mom and I