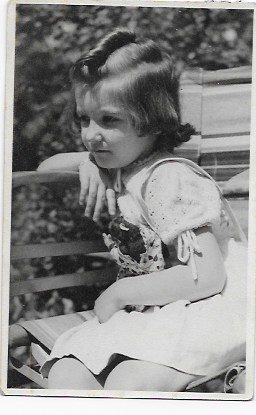

Dagmar with curled hair Little Micky

Those times were BP, Before Penicillin, and there were a number of serious childhood illnesses, which were expected for most children, like rites of passage. I only know from being told that my first severe illness, which had to have included some pain, was a kidney infection when I was just a baby. I don’t know how this was treated, but the after-effects would follow me into my teens due to my mother’s lifelong concern for my plumbing. “Don’t sit on cold concrete.” “Don’t sit on this cold metal bench,” and even more annoying, I was ordered to wear a pair of woolen knickers over my ordinary panties, so that I would not complain that they itched. Even though this loathsome garment was not visible under my skirts, I knew that it was there and I resented it and resented my mother lifting the hem of my dress, to make sure that I was in compliance, when I try to slip out the door.

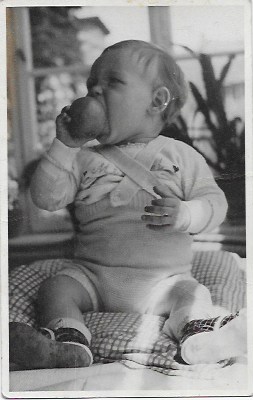

Both my little brother and I passed through the chicken pox without much drama, but he also came down with diphtheria. I do not remember details of his symptoms. The one I do remember was a high fever against which baby aspirin was an ineffective weapon. I remember that a few times he had to be wiped down with cool water and once immersed in water, then wrapped in a wet sheet. In those days the patient had to pass through what was called “The Crisis”, always during the night with one or both parents stoically sitting with the sick child, who would either survive through the night and recover quickly or in some sad cases, die. Micky lived.

Birthdays were grand occasions with family and friends gathered all around. The honoree’s chair would be decorated with garlands of greenery and flowers. Special little place cards, drawn and painted by my clever mother, told guests where to sit. Poems were recited and songs were sung in his or her honor. I probably was no older than three when, for my father’s birthday, my mother helped me to memorize a little poem she had written. Lifted onto a dining chair, I recited it for him and his guests to gentle applause. Before I could be lifted off the chair, I announced that I knew another poem and recited a two-line zinger that my Aunt Erna had secretly taught me. “ Scheisse im Trompetenrohr kommt Gott sei Dank nur selten vor” (Shit in the pipe of the trumpet luckily happens only rarely). This brought down the house and I was swiftly returned to the Kinderzimmer (children’s room) and to the tender care of Angela, before I could get into more mischief.

For my own birthdays, which I naturally remember best, there were singing and dancing and games and of course cake and candles and place cards and party favors and lots of guests. From my father’s side came my grandparents and my Aunt Lucy with her children, my cousins: Edgar, a little older than I, Marlies, about my age, and little Tessa. Their father, my father’s brother, had been inducted into the military early and was soon killed in battle. There was also Peter, with his mother, who were maybe the token poor relatives. Peter was a shy and quiet boy, who for reasons I do not know, did not have a father. The visitors from my mother’s side were my grandparents, Oma and Opa (my grandfather died young from cancer of the throat when I was about five years old), my mother’s sister, Aunt Mimi with her husband, my Uncle Emil. He was still young but already bald. They had three sons, Jurek, Felix, and Marian, my beloved cousins, 2, 5, and 9 years older than I, respectively. Also present was my Uncle Hansi, my mother’s 14-years-younger brother and only a year or two older than his nephew Marian. Finally, also invited to my birthday parties was Babette, my little day-to-day best friend, who lived in the villa across the street.

A very important member of the family and always present at family celebrations was my Aunt Erna. She was not a blood relative but both my brother’s and my godmother. I was told later that my father boycotted our christenings. He had, by that time, officially left the Roman Catholic Church, as many people had, either because the new ideology was hostile to religion, or because he was too stingy to pay church taxes. Aunt Erna was my mother’s best friend from their days together as teenagers in a finishing school in an Ursuline cloister, where apparently, she had been the terror of the poor nuns. Her escapades were legendary and provided stories throughout our growing-up years.

Aunt Erna would become even more important to us at the end of the war, as you will soon hear. She was a petite and good-looking young woman with an enterprising spirit and boundless energy and beloved by all for her generosity and great sense of humor. I can only remember seeing her in a dress once, a dress that my mother had sewn for her. She favored tailored clothes, suits and fedora hats. She had been engaged to marry once, but the wedding was called off at the last moment for reasons I never knew. Her parents, no doubt relieved that their unconventional daughter was going to be domesticated after all, had spent a great deal of money on a trousseau. I believe if Aunt Erna lived today, she might have lived as a lesbian.

The other highlight in the ritual calendar of my childhood was Christmas. On December 6, St. Nikolaus ushered in the season along with his rough servant Ruprecht in a kind of good-cop, bad cop routine. He would bring goodies to the good children while Ruprecht would bring coals to the not-so-good. Like every other child in Germany, I put my shoes, not my stockings, outside the door to my room at bedtime. I would jump out of bed the following morning to see what had been deposited in them. Usually, I got an apple and maybe some nuts in one shoe and a couple of coals in the other.

About this time, the Advent Wreath would appear floating over the center of our dining table, suspended on four strands of red ribbon from a red-painted wooden stand with a gold star on the top. On a fat circle of fir boughs stood four candles; the first one was lit on Sunday four weeks before Holy Night and an additional candle each Sunday following, until all four were burning just before Christmas.

During those last few days, the French doors to the dining room would be conspicuously shut, and secret proceedings went on behind them. Now my parents took their evening meal on a small table in the Herrenzimmer (gentlemen’s room) as we called our living room, maybe harking back to the days when men’s and women’s quarters were segregated, as they still are today in some Muslim countries. On Christmas Eve, after our meal of fish soup or baked carp, the doors to the dining room were finally opened. The tall Christmas tree in the corner, usually occupied by a spindly rubber tree plant, was decorated with heirloom glass ornaments and white burning candles and filled the room with golden light and the honey smell of the melting beeswax.

The effect was magical. We stood around the tree, singing Christmas carols, not only German ones but also the hauntingly beautiful Polish songs of my mother’s own childhood. I cannot remember many Christmases without some little twig getting singed or even catching fire, which added the delicious scent of burning conifer to the festive aroma. These little fires were quickly extinguished without much alarm. There never was any real danger, as the candles were not let burn long and the tree was never unattended. At last, the candles were snuffed out, and we could now turn our attention to the gifts which the Christkind (Christ child) had brought. I remember my gifts being modest and becoming more so as scarcity set in. I would get books and dolls, which I already owned and which had disappeared without my having noticed, and which were here again, spruced up, repaired and decked out in new clothes, that were often tiny copies of my own outfits.

For such festive occasions, it was not enough to deck me out in my best finery. My mother felt she had to do something about my hair, which she complained grew as straight as chives. This was to be improved with the help of a metal curling iron, which would be heated in the kitchen over a flame on her gas stove. It was always left there too long. When it started glowing red, its temperature was tested on a piece of newspaper and the kitchen promptly filled with acrid smoke. Then the iron was allowed to cool a little before my mother tried to curl under the straight-cut bottom of my chin-length hair. I, always worried that she would burn me, fidgeted, and twitched. Consequently, I was always burned a little, but never seriously enough for my mother to give up on that idea.

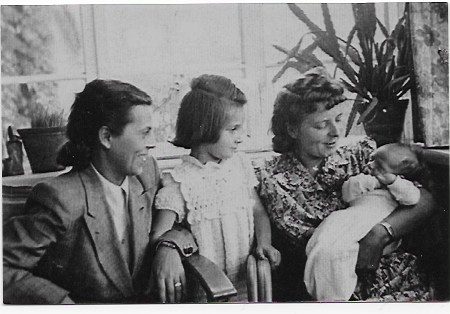

Dad and Micky My Mom (on the far left) and her companions

Two Aunts